OK, maybe it’s a bit weird to write a post about why we are NOT likely to invest in a sector, but I think it could be useful — so hear me out. First, we have done a ton of analysis to come to this conclusion. And if someone building legal vertical SaaS can prove us wrong, I’m all ears. And second, in the spirit of transparency, I hope that founders will find it useful to see the process we go through in evaluating a market. Vertical SaaS is a hot area right now, and we have lots of conviction around the idea that creating SaaS for a niche sector makes complete sense. But that doesn’t mean we will invest blindly in any vertical SaaS offering that has a strong narrative or early traction. The first in a series of verticals we will share our thesis on is legal.

So how did we decide to dive into legal vertical SaaS?

We have a team of investors focusing on vertical SaaS. But the potential market for this tech is huge, so narrowing it down to a small number of verticals is an important part of our approach. We want to know a market almost as well as the founders in that space before we invest. And we need something to help us determine where to invest our time as we go deeper to develop a strong point of view.

The starting point for this approach is data. This post tells you more about the methodology we used to prioritize our verticals. But in a nutshell, our goal is to identify sectors with the highest chance of spawning a breakout vertical SaaS company. We know from studying and investing in vertical SaaS businesses that winners have thrived in fragmented markets, usually replacing pen and paper processes with digital ones. As a result, it made sense to look for fragmented markets with low efficiency (which usually correlates with degree of digitization). This top-down, data-driven analysis pointed to legal services as being a particularly attractive vertical to dig into.

But we still needed to do bottom-up analysis to see if all the market dynamics at play would allow a new entrant to follow the vertical SaaS playbook and achieve a venture-scale outcome in our desired timeframe.

What do we mean by “vertical SaaS playbook”? From our experience studying and investing in vertical SaaS businesses, we know that there is a tried and tested playbook for success. We also know that this playbook may end up being rewritten by AI, and that’s exciting. But for now, to be successful in vertical SaaS you need three things, in this order:

To become a control point in the customer’s tech stack.

These ‘systems of record’ are the center of gravity for data and workflows and are essential pieces of a customer’s tech stack — they’re not ‘nice-to-have’. Of course, when it comes to vertical software, there are also many point solutions. But the most valuable vertical SaaS companies are built around control points because they offer strategic advantages that can lead to sustainable competitive moats and increased value creation (e.g., through product expansion, customer lock-in, data advantages, economies of scale, network effects, etc.).

To be able to expand the product offering to adjacent areas. Think Toast: it may have started as a point of sale (PoS) system, but it expanded to facilitate online ordering, inventory management, workforce management, payroll, and more.

To extend through the value chain. Not only will the software be valuable for the initial target market, but it will also have the potential to add value to the whole ecosystem, from suppliers to customers, or maybe even acting as a marketplace for the ecosystem.

For us to pursue a particular vertical, we need to see a pathway for a new entrant to achieve $100M+ topline within ~10 years using this playbook.

Our hunch was that within the legal vertical, there would be different segments, but that at least one of those segments would tick the box for all three criteria. We were wrong … let me tell you why.

But first, one important caveat: the legal vertical was explored specifically within the context of vertical SaaS. just because we’ve come to the conclusion that there isn’t an opportunity for us to invest in there doesn’t mean we think legal tech in its entirety is uninvestable. There are other segments of the legal tech market that could prove to be compelling, including even consumer-facing tech-enabled service companies. This just falls outside of our vertical SaaS investment mandate.

Before I dive in, for the purpose of our research, we viewed ‘legal services’ as two distinct markets — law firms and in-house legal departments — each with its own sub-segmentation. For example, large law firms are different animals than small and mid-sized law firms. We grouped small & mid-size law firms together because:

The line between them is blurred; everyone has a different definition.

They practice / operate similarly (though they have scale differences, which increases the complexity of sales & implementation, etc.).

Vendors targeting one segment typically target the other as well.

There are 175K law firms in the US (most recent US Census data available is 2018. Based on historical growth patterns, it’s unlikely to be materially different today). Only a thousand are considered large (with 100+ lawyers). The remaining 174K are all small and mid-sized, with the vast majority (130k firms) having fewer than 10 lawyers.

In aggregate, US law firms generate $300B in revenue/year. There is incredible revenue concentration towards the top, with the top 200 firms making up 50% of industry revenue. Law firms spend about 4% of revenue on tech. That’s a total tech TAM of about $12B. Most of that is attributed to the large law firms. Law firm margins are getting compressed, so law firms tend to be price-sensitive when it comes to tech. And there’s not a lot of room for those budgets to grow.

What the research showed: large law firms

It made sense to start with large law firms because that’s where most of the spend is. However, knowing that one appeal of vertical SaaS as a venture-backable business is sales efficiency, we quickly concluded this is not where you’re going to find it.

“Decision-making in law firms is incredibly inefficient and unproductive, which makes it really hard to fund and deploy new technologies. Unless you reward the firm and individual employees for being innovative, they never will be.” — Chief Data Scientist, AmLaw 50 firm.

The sales cycles are long and complicated with strict security requirements. Many large law firms told us they’re wary of working with startups, often eliminating them during vendor consideration. Several C-suite execs we spoke with explained how they had gotten burned in the past by working with startups that were quickly acquired and their products and support services deprecated.

From a vertical SaaS perspective, there’s also not a lot of room for a new player to make headway here — there’s no clear control point to be exploited today. The core components of the tech stack are solidly entrenched by large, established players like Microsoft, iManage, Intapp, Thomson Reuters, and Litera.

Most large law firms have a basic tech stack comprised of:

Microsoft 365 — primarily Outlook, Office

Document management — iManage, NetDocs

Client intake & Conflicts — Intapp

CRM — Salesforce, LexisNexis InterAction

Finance system — Thomson Reuters’ 3E Elite, Aderant

Document assembly & automation — Litera

eSignature — Docusign

HR systems — Workday

Collaboration tools — Teams, Zoom

Infrastructure stack

Security stack

Then there’s a whole variety of practice-specific apps and services like eDiscovery (Relativity), docketing software for specific practice groups (for example, CPI for patent/trademarks), etc.

The best way in (for a new entrant) is as an incremental point solution, with Microsoft and other entrenched players being gatekeepers vis-à-vis integration, with little opportunity to expand outward in the law firm’s tech stack. To achieve a venture scale outcome, these point solutions may need to expand out of the legal vertical and into broader professional services (e.g., consulting). In our view, those end up looking more like a horizontal SaaS than vertical SaaS businesses, which doesn’t mean they’re unappealing, they just fall outside of our vertical SaaS purview.

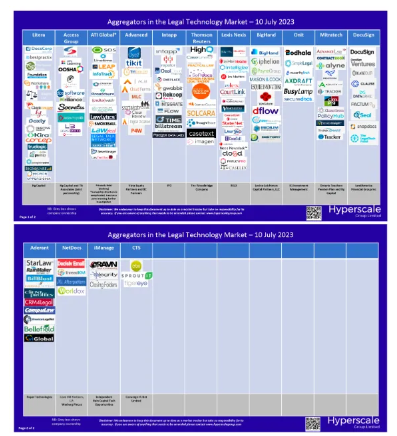

Also, historical precedent has shown that legal point solutions that succeed in making headway are usually quickly acquired by an incumbent platform at a low price before they’re able to achieve real scale. The images below clearly demonstrate the ‘platformization’ trend underway (and there have been even more M&A announcements since this was last updated a month ago!).

“If you invest in a startup targeting the large law firm segment, you’re playing for ultimately an acquisition by Litera or Thomson Reuters or some other PE roll-up — there are probably a very small handful of plays that have delivered 10x to VCs.” — Director of Practice Innovation, AmLaw 50 firm

Source: Derek Southall, Hyperscale Group Limited

Large law firms, bogged down by proliferating point solutions, are actually calling for platformization. One AmLaw 50 firm’s CTO told us, “We have very strict security requirements; everything needs to be Microsoft-level. We increasingly can’t manage the security infrastructure for hundreds of point solutions. We’d rather have a few large platforms.” Another firm’s CIO pointed to budget considerations, explaining that VC-backed point solutions pressed for growth have turned to unjustifiable price hikes (30–40% y/y!), which have become harder to rationalize internally. “We’re already at our budget ceiling,” he said, “so now we’re being forced to consolidate and do more with less.”

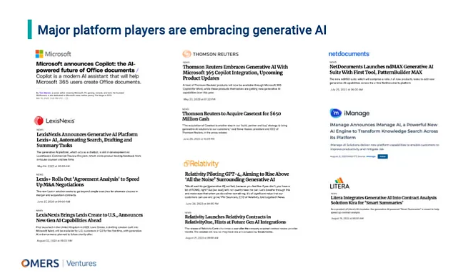

In addition, many of the major players are embracing generative AI. Some may say this is the natural place to look for exciting startup potential, especially in the legal field where large language models can be uniquely applied. But based on our conversations, we believe new entrants here will struggle to build defensible moats and will have to work with the legacy players (who have the inherent data advantages) to create real sustainable value for users. This would likely lead to a niche point solution outcome, a horizontal expansion path (i.e., to other industries), or a quick, subscale exit. None of these outcomes are interesting to us as vertical SaaS venture investors. As an aside, because we know it will be asked, industry experts we spoke with all believed Thomson Reuters’ recent $650M acquisition of Casetext would prove to be an extraordinary outlier.

What the research showed: small and mid-sized firms

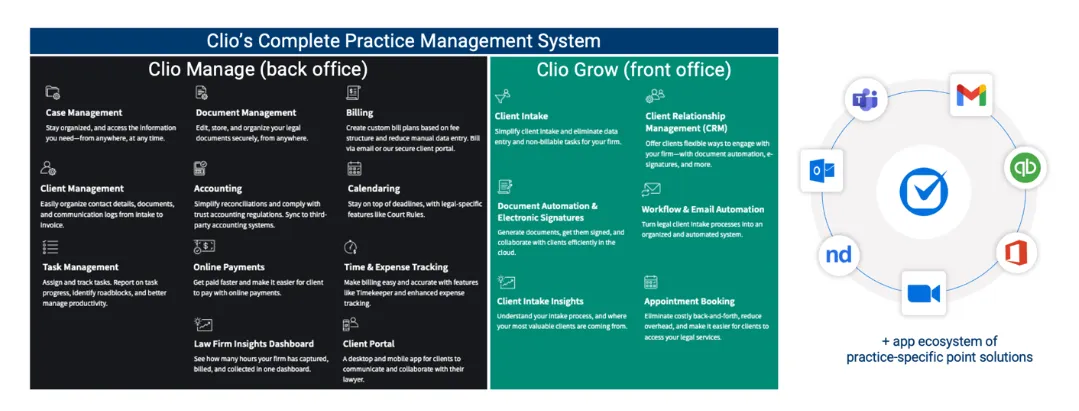

The small and mid-sized segment is more supportive of a vertical SaaS playbook — own a control point, expand multi-product, extend through the value chain — and is where current VC-backed market leaders have thrived.

The practice management system is the control point in this segment, which is where Clio* dominates with a long and growing list of competitors. Practice management is time tracking, billing, and invoicing at its foundation, but the category has expanded to include most other aspects involved in running a practice (e.g., client intake, appointment booking, document management and automation, etc.).

This is a well-established area (some might say commoditized) and folks are now competing largely on price. Based on our research, the opportunity for investment in new, early-stage entrants in this space that have a real shot at $100M ARR within the next 10 years is low.

As with any established market leader, there will be those who suggest Clio’s market share is ripe for disruption. Our opinion is that this would be an uphill battle. A company would either need to replace Clio, or, if targeting a firm that has not yet digitized, would need to educate them on the benefit of digitization and then select their product over the clear market leader.

And even in the small and mid-sized segment, sales and implementation cycles are longer than people think. There’s not as much uniformity/repeatability as we believe is necessary to build a winning vertical SaaS company. Adoption is critical to success, and changing behavior in this market is an uphill battle.

The reason it takes so long is because of the opportunity cost: law firms need to have the downtime to train their staff (and since they’re at an hourly rate, it gets expensive) as well as downtime for data and document migration. All in, implementation could be 6+ months. We heard consistently that the number one downfall is adoption. If you can’t get customers from sales to onboarding as quickly as possible, you’re going to have a lot of challenges with adoption. And in this segment, the onboarding process needs to be very handheld, which can be both time-intensive and expensive.

Outside of practice management — which seems to be the only natural control point and the lion’s share of small/mid-sized firms’ tech budget — a legal vertical SaaS company, likely a point solution, would have to own the small/mid-size market and then cross into big law to have a venture-scale outcome. This has proved to be incredibly difficult, with no real success stories to point to. The only ones who play in both markets at scale are the big platforms we’ve already mentioned (Thomson Reuters, Litera, etc.).

As an aside, several people we spoke to mentioned some changing state regulations allowing non-lawyers to own law firms. They think it could lead to increased adoption of tech, but also to industry consolidation. This may well be an area to watch, but it’s too soon to gauge market potential right now.

What the research showed: in-house legal departments

This area is easier to summarize because we believe that although there may be viable opportunities targeting in-house legal departments, they fall more into the horizontal than the vertical SaaS bucket. And here’s why:

It’s not truly a vertical; it’s a department. Solutions targeting the legal department are not creating a system of record for the entire company/enterprise, which is the goal of vertical SaaS.

A legal department’s goals, challenges, decision-making/buying power, etc., are incredibly heterogeneous from company to company. This results in lack of uniformity / challenging sales motion, which breaks the playbook for a typical breakout vertical SaaS company.

The expansion path is naturally horizontal (selling the same product to new companies, across industries) vs vertical (once you own the control point for the vertical, multi-product expansion with existing customers).

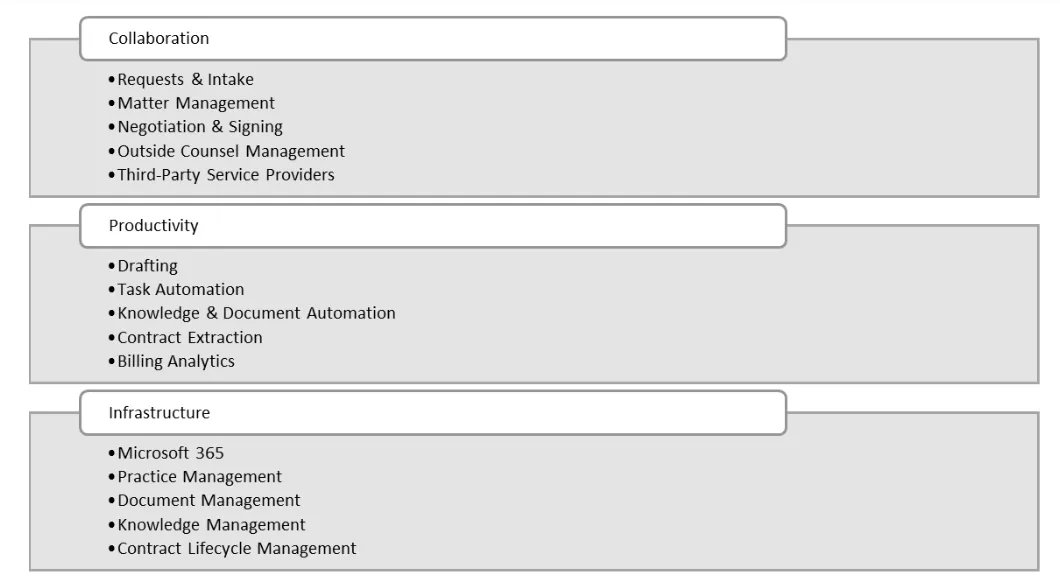

But here’s what we learned about the in-house legal department’s tech stack:

On top is the collaboration layer. This is relatively static with a slower sales/adoption cycle as it requires buy-in from other parties. Typically, the solutions here have no more than a 2–3-year lifetime.

In the middle is the productivity layer, comprised of systems of differentiation. Here, innovation happens quickly, driving a proliferation of point solutions (this is where generative AI is entering). Some have referred to this area as the startup graveyard because there’s a lot of competition and a lot of poorly designed products that struggle to garner adoption.

And finally, we have the big, expensive stuff in the infrastructure layer. These systems of record are notoriously sticky with 5–10-year staying power. The sales cycle may be slower and more difficult than the productivity layer, but once in, a business likely has better customer retention. There’s a lot of excitement around contract lifecycle management (CLM), in particular, but very few players truly facilitate the end-to-process. There are lots of point solutions here that end up needing to be stitched together.

Integration between the layers is important and not an area people pay enough attention to. Platforms like Microsoft are important in these scenarios as massive adoption without integration is likely impossible.

Not for us … right now

For all the reasons outlined above (and many more that I didn’t include), we’ve decided legal vertical SaaS is not a top priority investment area for our vertical SaaS team. What proof would we need to see to be convinced we’re wrong? A company owning a control point that is relevant to all or most small/mid-size practice areas, with a superior product and potential product adjacency. If a company came to us today with evidence that they’ve got 1,500 law firms (nearly 1% of the small/mid-size market) as customers, top-notch sales efficiency, high usage and engagement, a clear product expansion roadmap and potential to extend through the value chain, I’d be prepared to eat my words.

Now, there’s a difference between believing a technology will be truly transformational to an industry and believing there are investable businesses driving that transformation. For example, while we do believe generative AI will radically transform the way law is practiced, we don’t believe today that there’s an investable, legal-specific gen AI SaaS business that will get us a 10x return in 10 years.

We will continue to share breakdowns of the markets we consider whether they become priorities for investing or not. If you think I’m wrong on this one, or have missed something significant, don’t hesitate to let me know. you can reach me (Marissa Moore) at mmoore@omersventures.com.

*Disclosure, Clio is a portfolio company of OMERS’s growth equity portfolio.