The kind of AI that powers ChatGPT – transformer-based generative AI – is transformative (not meant as a pun, honest) and does indeed represent a tectonic shift in the ways in which we use and engage with technology. Just not in the ways most everyone thinks about it – or indeed, in the ways in which many are eagerly rushing it into production.

The main disconnect stems from the fact that the type of AI we created, specifically when it comes to transformer-based generative models, does not neatly fit the mental model of what we imagined truly competent AI would take when it arrived. And yet it’s close enough that it looks like that kind of idealized AI when you squint at it.

A couple of months ago, I was able to join CDL’s annual SuperSession event, which includes presentations from program graduates, as well as talks from outside speakers. One such speaker was Sendhil Mullainathan, a machine learning researcher and behaviorist, professor at Chicago Booth, and the co-founder of two different companies.

Mullainathan kicked off the day’s events with a presentation tackling four of the biggest myths being perpetuated about AI, and offering fact-based perspectives on what the actual truth of the situation is in each case instead.

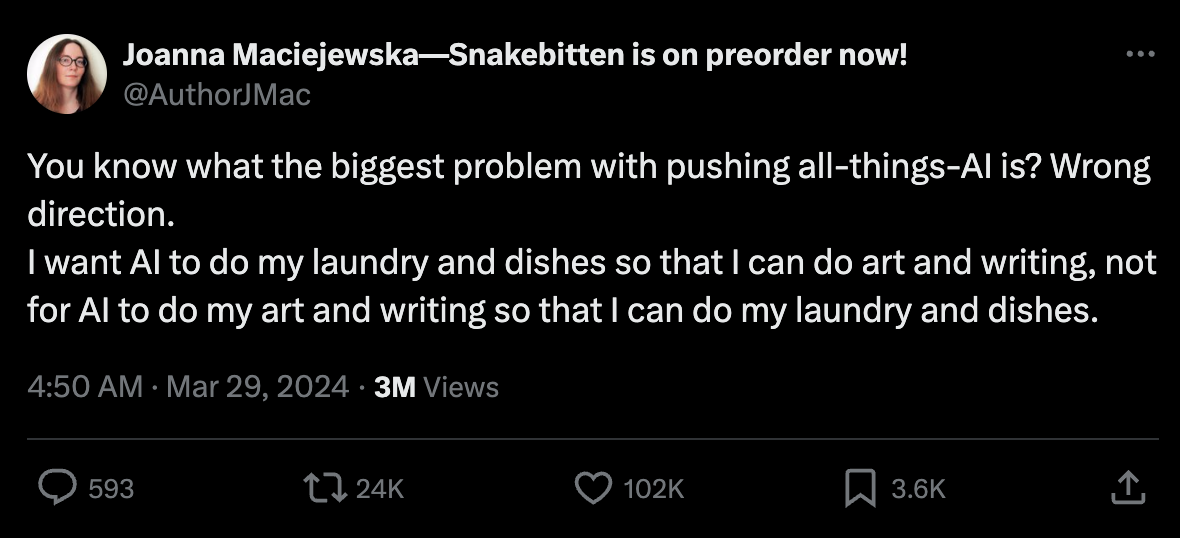

One of the myths in particular struck a chord: AIs are for simple tasks. We’ve probably all seen the wildly viral tweet by Joanna Maciejewska about AI boosters “pushing” it in the “wrong direction.”

Let’s ignore the fact that she’s talking about physical world manipulation here and focus instead on the spirit of the comment: AI should handle the toil and drudgery (aka ‘simple tasks’) so that we as humans can live fully in the lush sophistication of creative pursuits.

In practice, it’s increasingly evident that while ‘old-school,’ rule based AI (aka machine learning) is actually decent at automating some repetitive, menial business tasks, generative AI isn’t really great at this sort of thing. The baked-in LLM habit of ‘hallucinating,’ or generating a result that fits perfectly the strict terms of the request, but contains inaccurate or wholly false information, throws a wrench in the works more often than not when it comes to rote, mechanical business activities.

That was one of the key points Mullainathan made during his talk: Generative AI isn’t a simple task automaton – but that doesn’t mean, as I’ve seen others argue, that it’s a technology whose utility will naturally plateau or the value of which is overblown.

Rather, those building with this exciting new tech should be embracing what it is good at, which ends up being creative tasks – something that no technology that has ever existed prior has actually been able to do, let alone do well. I’m not talking about creative enablement tech, of which there is plenty; I mean creative in the generative sense, which is what makes gen AI so aptly named.

Mullainathan put it simply: We’ve never before had technology that could co-create along with us, as originators of creative works, rather than as enablers, accelerants or expression mechanisms. One of gen AI’s most significant – and least well understood – attributes is that it can produce new creative output, rather than just remix or boost what it’s provided.

There’s a rich, fruitful and necessary debate to be had about whether what generative AI is doing actually consists of novel creation, given that the fundamental ingredients for all the original foundational models was existing information produced by humans. It’s a nuanced and subtle debate with good arguments on all sides, but I think we can actually just sidestep it entirely for the purposes of talking about gen AI’s practical deployment in business and tech, and the ramifications it is having and will have in the future.

It’s enough for the purposes of this exploration that the outputs of generative AI typically look and feel like original, creative works – in a way that’s increasingly difficult (if not virtually impossible) to distinguish from those made by people.

This is new territory for us – and a change that I think is both potentially more profound than even something like the advent of computing, but also more likely to remain subtle and hard to detect until very late in the course of its actual impact. Just as we’re beginning to realize that the impact of climate change began well before we clocked it, and that is actually been changing things under our noses for an extended period of time, I don’t think we’ll know what gen AI hath wrought until – well, until it’s already well and truly wroughten.

While impossible to resist the homophone, I don’t actually think that the outcome of this shift and the ceding of our human exclusivity on creative acts will end up bad for us. The fact that we aren’t alone anymore as originators of creative output is thrilling, and rife with potential to launch us into paradigms for work and life that we could never, in our wildest dreams, have conceived of when we were flying solo as the lone agents of ideation.

What this all means for technology tooling and business building is a suggestion that we’re barking up the wrong tree – we’re pouring engineering talent, compute and dollars into building AI-powered executive assistants and paralegals, trying to shoehorn gen AI into a deterministic box with fixed boundaries. What we should be doing is maximizing its creative potential, to make the most of our newfound collaborative advantage with machines that make.